All products mentioned here are independently selected by our editors and writers. When you buy something through links on our site, Mashable may earn an affiliate commission.

Thomasin McKenzie as embryologist and nurse Jean Purdy in “Joy.”

A tender look at an incredible true story, Netflix’s Joy tells the story of the scientists who pioneered the research that led to the world’s first baby born via in vitro fertilization (IVF). Their research in the late 1960s and early 1970s changed the lives of many – ever since More than 12 million babies have been born as a result of IVF and other similar assisted reproduction technologies.

Directed by Ben Taylor, Joy is true to life in more ways than one, as the script was not only based on history, but co-written by Jack Thorne and his wife Rachel Mason. inspired due to their own fertility problems and experiences with IVF. Joy follows the lives of embryologist Jean Purdy (Thomasin Mackenzie), surgeon Patrick Steptoe (Bill Nighy) and scientist Robert Edwards (James Norton) as they battle opposition to their work from church, state and the media.

SEE ALSO: What is reproductive justice? Check out these resources to learn more about the movement.

But how much has really changed since then in terms of social stigma and discrimination surrounding fertility and pregnancy?

Joy focuses on the harmful social stigma surrounding fertility

Thomasin McKenzie as Jean Purdy as James Norton as Robert Edwards in ‘Joy’.

Thomasin McKenzie as Jean Purdy as James Norton as Robert Edwards in ‘Joy’. Credit: Kerry Brown/Netflix

Joy provides a telling snapshot of the ways in which societal attitudes hindered the progress of IVF research and the establishment of IVF research Bourn Hall Fertility Clinic in Cambridge, and how these views personally affected not only the team who worked on it, but also the women who courageously volunteered to take part – they called themselves the Ovum Club.

As the project’s lead nurse and embryologist, Jean suffers in her personal life. She is excommunicated by her devoutly religious mother Gladys (Joanna Scanlan) and the church community for her work, and is especially criticized for working with Steptoe, who at the time was part of a minority of doctors who performed legal abortions, to the outrage of many. . We even see Jean grapple with the tension between abortion and her faith, with one poignant scene in which operating room supervisor Muriel “Matron” Harris (Tanya Moodie) reminds her of the overarching importance of offering women choice – whether that means having a have to make a choice. chance of getting pregnant with the help of science or of terminating a pregnancy.

Thomasin McKenzie as Jean Purdy in ‘Joy’.

Thomasin McKenzie as Jean Purdy. Credit: Kerry Brown/Netflix

Jean and Robert suffer tremendous harassment in the film, with Robert being harassed on live TV, taunted on the street, and called “Dr. Frankenstein” for his efforts, with the words painted on the exterior walls of the clinic. The women involved in the experiment (brought to the screen by actors like Derry girls star Louisa Harland as Rachel, Bridgerton‘s Harriet Cains as Gail and Carla Harrison-Hodge as Alice) are also not safe from society’s judgment, or from the stigma surrounding fertility (and infertility). Newspapers hound them throughout their treatment, offering the scientists thousands of pounds for their names and addresses – all in the service of violating their privacy to shame them for their choice.

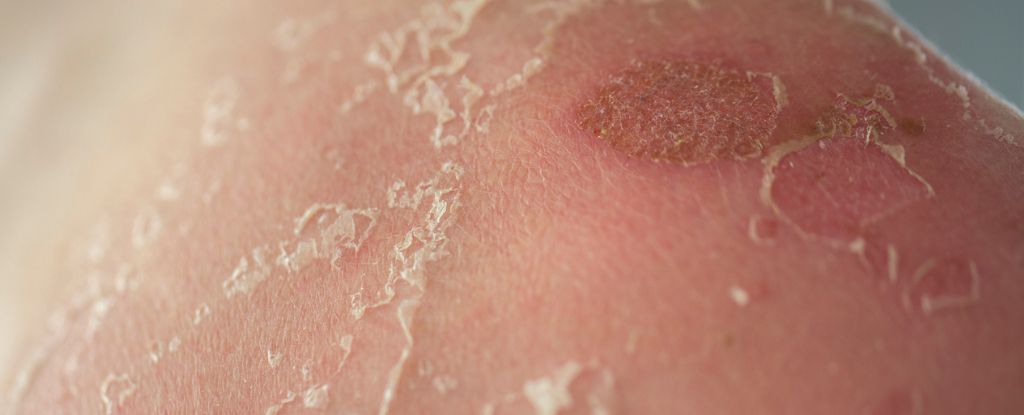

The film’s exploration of infertility is personal to the protagonist; Jean’s ongoing problems with endometriosis and infertility play a key role in this Joy. Endometriosis – a gynecological condition that makes it more difficult to become pregnant – is being investigated to this day, and even more so in the 1960s and 1970s, creating shame among women who were made to feel like it was their fault that they couldn’t get pregnant. Jean elaborates on this in a heartbreaking scene, explaining that so many women (herself included) feel lost without this ability, whatever the cause. Not only is patriarchal society vilified for seeking IVF as an alternative, but patriarchal society also defines the value of these women through their ability to become mothers – an attitude that prevails today and continues to increase the stigma surrounding pregnancy, fertility and promotes infertility.

Where does fertility stigma come from?

Unfortunately, fertility stigma is as deeply entrenched in our history as it is in our modern culture. For example, noble women in medieval Japan faced judgment within their marriages if they did not produce children, while 19th century France saw doctors accusing women who had no children of promiscuity, venereal disease and abortions. Even as recent as the mid-20th century – around that time Joy is set — women were accused of committing ‘adultery’ if they were conceived through artificial insemination with donor sperm. The suffering and vilification of women as motherhood is seen as the ultimate mark of femininity, and traditional methods of conception prioritized over women’s health and well-being can be traced through the centuries.

The impact of the law on our reproductive choices

A protester in Trafalgar Square, London, in 2022 following the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade.

A protester in Trafalgar Square, London, in 2022 following the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v Wade. Credit: Vuk Valcic/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Since that time we have seen a shift in attitudes towards fertility and pregnancy Joy has been set. However, we’ve also seen this in a variety of ways, enshrining it into law and limiting the way women make decisions around their bodies – the most prominent example being the US Supreme Court ruling. overturning Roe v. Wade in 2022 and subsequent state abortion bans.

In October, after heavy campaigns, Britain England and Wales have passed a law mandating safe access buffer zones within a 150 meter radius of all abortion clinics. This will provide protection for women accessing this healthcare, with activities intended to influence women or that cause intimidation, alarm or fear all prohibited by law. Reports harassment continued until the ban British Pregnancy Advice Service (BPAS) CEO Heidi Stewart reports that women are being called “murderers” and leaflets are being pushed to them falsely claiming that abortion causes breast cancer.

Stewart describes the buffer zones as “a critical step to ensure women have access to essential health care without fear, shame or intimidation.”

But Stewart is clear that there is much further to go to combat fertility and pregnancy stigma, noting the importance of “remaining vigilant and relentless in protecting women’s abortion rights” – a sentiment shared by the US-based Center for Reproductive Rights.

In the US, this stigma remains increasingly volatile and threatening, especially now that Donald Trump has been re-elected in November. played a key role in Overturning Roe v. Wadecausing abortion to almost or completely occur banned in 17 states.

SEE ALSO: How to support reproductive rights in the US from outside the US

“If reproductive rights issues continue to fester in silence, the stigma grows,” Stewart explains. “If the ongoing events in the United States have taught us anything, it is that silence about reproductive rights is no longer an option.”

It is crucial that such attitudes and actions are questioned to quell the spread of stigma on both sides of the Atlantic, so that the choices the team represented Joy that are fought for are protected for all women.

How fertility stigma affects women’s experience in the workplace

We also know that this type of discrimination does not only concern a person’s attempts to become pregnant or their decision to terminate a pregnancy. Joeli Brearley, CEO and Founder of Pregnant and then screwed (PTS) — a charity committed to ending “the motherhood penalty‘, which covers the impact motherhood has on women’s careers, says their experiences and advancement in the workplace are also affected.

“Women are seen as distracted and less committed to work from the moment they become pregnant,” she explains. “So we need managers who are trained in unconscious bias and who understand the business reasons for caring for pregnant employees.”

Brearley adds that women appear to be afraid to discuss fertility treatment with their employers, for fear of discrimination. “According to our research one in four women undergoing fertility treatment experiences unfair treatment as a result” says Brearley. Once women return to work after having a child, the situation does not necessarily improve – according to research by PTS77 percent of women experience discrimination when they return to work. “It’s not a mother’s problem, it’s a social problem,” she explains.

The pioneer team represented in Joy faced such reactions and treatments, as did the self-styled Ovum Club of women who took part in the early IVF trials. Their fertility was dismissed as a serious and impactful health problem in the 1960s, with personal, private choices around pregnancy being made fodder for the public to debate. And decades later, we are still not out of the woods. Much more needs to change before the stigma is truly lifted and women can feel free.

“When women can make these deeply personal decisions without fear of public judgment or confrontation,” says Stewart, “we are affirming their right to choose and reinforcing that fertility and pregnancy choices should be free from stigma.”

Joy is now streaming on Netflix.